A visit to the Flinders Ranges in outback South Australia is one of my favourite camping trips; an opportunity to enjoy the solitude of Australia’s haunting and ageless landscape, distinct flora and fauna, bushwalks, ancient rock art and more. One visit is not enough, as the Ranges cover a vast area, stretching over 400 kilometres.

On the way from home near Melbourne, I stay at campsites on the banks of the Murray River, at quaint and quiet country towns, or in some of South Australia’s prime wine regions like the Barossa Valley and Clare Valley. Tasting wines before camping in the desert has a certain piquancy.

The tranquility of the Murray River is occasionally broken by a flotilla of pelicans gliding by the campsite, or a passing houseboat.

Burra is an appealing South Australian country town close to the Ranges. Typically, it has grand buildings, a characterful pub, and fine streetscapes, a testament to a more prosperous past; in its case, copper mining.

Another classic country pub at Peterborough.

Bush camping at Wilpena Pound in the Flinders Ranges. The billy is boiling on the open fire while the solar panel charges the battery to power the portable refrigerator and lights.

Emus wander through the camp, at home in an arid environment.

Red gums line the creek beds waiting for infrequent rains to flood the watercourse.

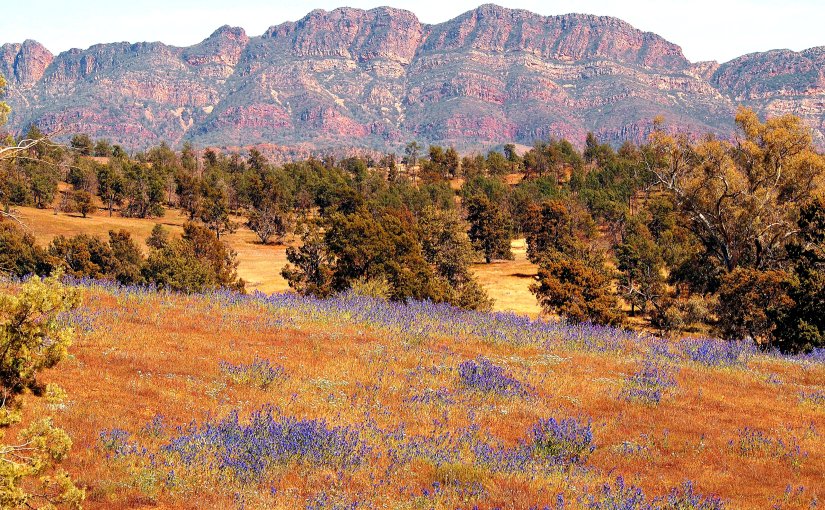

A walk or a drive provides these views.

Ruined stone houses are common around the Flinders Ranges. European settlers established farms in the nineteenth century and misunderstood the Outback climate, believing that a good season or two was typical. Ultimately, the usual drought-like weather conditions prevailed and within a generation, most small settlers were ruined. A tragedy for them, but worse for the Aboriginal people who were displaced by the settlers, after living in the area for tens of thousands of years.